Johnny Aitken: Artist

Recent Press

the Gift: transformation tour 2019

The Gift

“Hello, my name is Johnny Aitken. I did not speak until I was eighteen years old.”

Everyone has a story. The Gift is one person’s journey through challenge and adversity in a boy’s early years. He is too young to understand the world he has been born into and has no voice to express the turmoil of his circumstances. For a boy without words, we use drumming, singing, movement and sound effects in a series of short scenes to evoke significant events in his life. As in a dream, Indigenous symbols and metaphor tell this tale of evolution and ultimate celebration. Some scenes will be easy to decipher, and some may leave you perplexed. It is all part of the experience.

Promotional Preview of The Gift.

During the period when I did not speak, in order to communicate I used to point, and I used facial expressions. These two techniques have been integrated into the piece where possible, to help demonstrate my vulnerability at such a young age. Although I did not speak, I did make what I now call “cave man” sounds, this is used in one humiliating scene where “bogey-woman” is attempting to get me to speak. Each scene communicates to the audience key moments which would transform my life. The path to where I am now.

Photo Credits: Roy Mulder

Press for The Gift

Eight years in the making, Surrounded By Owls Productions’ The Gift is the heart-wrenching and transformative autobiographical story of co-creator and co-star Johnny Aitken’s youth.

Using brilliant facial expression, movement, song, and a drumbeat steady as a heart, Aitken (Coast Salish) and co-star Shelley MacDonald (Mi’kmaq) piece together fragments of his memories to bring their audience into a vivid dream-like state. They tell a story that too many indigenous families across Canada can relate to: a family traumatized by addiction, abuse, silence, and death, all stemmed from the violence of colonialism. Recognizing the heavy impact the show may have on their audience, the duo opens the floor into a talk-back in lieu of a talking circle for their last twenty minutes, both to unpack what was witnessed and answer questions that inevitably arise in an unspoken piece.

This last component is key, as the intents of all the piece’s phases are not immediately obvious, especially to those who haven’t experienced trauma of this nature.

Bottom Line

The Gift invites its audience into a deeply emotional story of trauma but also of transformation and growth. If you have an open heart and appreciate strong symbolism and body expression, this is a show for you to see.

Janis Lacouvee

In the blink of an eye, Johnny Aitken transforms from strong adult, wrapped in four-point blanket with drum in hand, to a shy mischievous child, peeking out. A sudden low rustling and rattling brings fear to his countenance; he scampers off. From the shadows, a lurking faceless ghoul moves slowly across the stage, breath heavy and sustained—a powerful embodiment of evil.

The Gift is visceral and at times harrowing, the emotional impact felt all the more heavily for being unmitigated by language. Audience members will bring their own backstory forward into the interpretation of the sequences—trauma and abuse are vividly portrayed. Darkness and light co-mingle—there are many moments of tenderness, the child rocked and lulled to sleep by a mother’s gentle singing. The carefully prescribed movements of the actors, sharp boom of drum and re-enactment of ceremonial smudging carry weight and demand attention.

Evil walks the earth yet love endures and happier memories can sustain. Aitken’s struggle with profound grief at the death of his mother, and conflicted state at the death of his father is elegantly enacted—will he be gobbled by the voracious energy of the dark, or move forward into light?

At the discussion after the show Aitken is quick to point out “I’m ok”, and speak of the responsibility to help audiences unpack the experience.

In this Year of Reconciliation, The Gift represents an important opportunity to bear witness and to move forward in the journey. The story of this one small mixed Indigenous/settler boy resonates deeply. Sincere thanks and respect to the artists for taking painful personal experience and making impactful art.

“My name is Johnny Aitken; I did not speak until I was eighteen”. Learn more about his story, the inspiration for The Gift. Johnny Aitken is part of the 2017 Indigenous Artist Program which mentors a participating artist who is producing a show as part of the Victoria Fringe Festival.

How long have you been producing work on the Fringe circuit? As an artist/company?

This is my first Fringe Festival. I’ve performed on many of the Southern Gulf Islands, Presentation House Theatre in North Vancouver, Intrepid Theatre in Victoria BC and two performances at William Head Prison in Victoria.

Have you been (or will you be) taking the show to other Fringes?

After the Victoria Fringe Festival, The Gift will be performed on Salt Spring Island at ArtSpring Theatre on September 28th for one performance, presented by Graffiti Theatre of Salt Spring Island.

My hope is to have The Gift booked by theatres to present as part of their season. I currently have no plans to take to other Fringes but would love to perform where the Fringe Festival began: Edinburgh.

Can you speak to the creation process of this work?

This piece of theatre started in 2010 after a casual conversation with Gail Noonan on a BC Ferry. It came up in conversation how I did not begin to speak until the age of 18, a couple days after this conversation, Gail called me up and asked if there was a possibility of creating something theatrical with this fact. Gail and I spent 2 years developing this piece to get it to the point of what it is today. Gail and I decided early on in our process that we needed to be responsible as artists to include an opportunity for audience members to debrief after watching this emotionally intense piece of theatre: the birth of including a talking circle

Who will your show appeal to?

This show will appeal to all nationalities, it is a universal piece of art. Because there is no dialogue in the piece, it does not matter what language one speaks. This piece has been performed for a grade seven class, recommended for ages 14+ (PG)

What would you say to entice a potential audience member to come?

To entice someone: this piece is different by default, it has not dialogue. The piece uses movement, dance, vocal sounds, drumming and stomping to tell the story. It is performed in a “dream-like” state (because all scenes are fragmented memories of a young boy (experiencing complex trauma).

What do you hope to inspire in your audience?

I hope people will leave this piece of theatre with the sense of joy.

A performance such as Johnny Aitken’s The Gift is difficult to review. His dance-theatre piece (created with fellow Mayne Island resident Gail Noonan) reflects the terrible suffering he underwent as a child. His alcoholic father used to regularly beat his mother, an Indigenous woman. Aitken, also physically and mentally abused, was so profoundly traumatized he didn’t speak until he was 18.

The Gift, performed with Shelley MacDonald, is Aitken’s artistic response to his shocking past. For 70 minutes the pair offer a mysterious movement performance, mostly non-verbal, with virtually no music (there are moments of drumming and singing). It’s like witnessing a ritualistic ceremony. The bare-foot Aitken, dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, alternates between fleeting moments of joy and, more often, sequences in which he appears anguished, sometimes curled up on the stage in a fetal-like position.

A few scenes are literal. At one point the pair play ball; there’s a cleansing sequence; elsewhere a handful of change is scattered on stage. Yet more typically The Gift is abstract, replete with portentous heavy breathing and slow movement.

Viewed strictly as an artwork, The Gift succeeds only partly. In technical terms, the level of dance is rudimentary. The show is too oblique, too slow-moving — and too long. Tellingly it only made sense (or at least more sense) afterwards, when Aitken — a gracious and genial fellow — explained his background in a question-and-answer session.

That said, some attending Friday’s show were obviously moved by The Gift. One woman left in tears half-way though.

You might have the same reaction. Here’s my (admittedy strong) bias: I believe dance and theatre should succeed primarily as a work of art, regardless of the therapeutic value they may provide. Others will adamantly disagree and may find The Gift a powerful experience.

The Gift gives voice to recovery from childhood trauma

Mayne Island artist/performer Johnny Aitken says he didn’t speak until he was 18 years old.

It might be linked to his turbulent upbringing. His aboriginal mother, who died when Aitken was seven, was beaten by his father, an alcoholic.

Save for the rare utterance and occasional noise, Aitken didn’t say one word throughout his childhood and most of his teenage years.

On Friday and Saturday, the Coast Salish 48-year-old is joined by actor Shelley MacDonald for performances of his autobiographical show The Gift at Metro Studio.

Through movement, drumming, dance and mask work, the 50-minute piece tells the story of Aitken’s growing up and how he eventually found his voice.

Aitken’s father, a Scot, died when his son was 13. After that, Aitken was placed in ministry care. When he turned 18, his case worker presented an ultimatum.

“She said: ‘John, you’re going out of care. I’m not going to be working with you any more. You either learn to sign or you begin to speak.’ So I decided I needed to speak,” he said.

Before that, Aitken, one of six children, had relied on others to communicate with the world. At restaurants, for example, he would either get someone else to order for him or just use his finger to point out menu choices.

Forcing himself to talk in his late teens was difficult. The words didn’t come easily. And Aitken had trouble with some sounds, such as the letter R. He recalls once asking a waitress for a Sprite and being teased about his mispronunciation.

“That’s just one clear memory I have. I knew it was going to be difficult,” he said.

About this time, he moved to Victoria, where he lived for about a decade. Aitken had started hip-hop dancing at age 15. In the city, he began studying dance with Stages Dance and Lynda Raino.

“The dance was great,” he said. “It was another way of me expressing myself, because I didn’t have to say anything.”

Aitken was particularly impressed with Raino, who became a mentor. He never forgot once rehearsing with her and witnessing the utter sense of abandonment Raino put into her dance.

“She showed me at that moment what I need to do with my own physical body. Whenever I’m on stage, every fibre, every essence of me is engaged.”

Aitken created The Gift with collaborator Gail Noonan, a Mayne Island animator. The partnership came about following a B.C. ferry ride during which Aitken mentioned to Noonan how he had been silent until his late teens.

Several days later, she contacted him about the possibility of creating a theatre piece inspired by his unusual story.

He agreed immediately. Yet Aitken admits during the early stages of The Gift’s creation, about five years ago, he often felt like dropping out of the project. Reliving the past was more painful than he thought.

“I was being triggered. There was stuff, especially to do with my dad. There was a lot of dad stuff,” he said.

In Victoria, Aitken trained at Camosun College to be a nurse’s aide, and then a Indigenous family support worker. He’s also a carver and videographer.

Although well-spoken on the phone, Aitken said years of not talking left their mark. Today, he thinks before speaking, choosing only words he knows he can pronounce clearly.

“Even my partner says: ‘I don’t hear any speech impediment.’ I go: ‘Well, if you had me read from a book, you’d be able to tell immediately.’ ”

The Gift has helped Aitken recover from the emotional damage he endured as a child and a teen.

But, he said, the scars remain. Part of recovery has meant simply accepting he’ll never completely heal.

Nonetheless, The Gift — which has been performed at William Head Institution, as well as in Vancouver and on Galiano and Pender islands — is intended to show a good life can follow years of family dysfunction.

“The piece is ultimately about celebration,” Aitken said. “You can go through all this violence and you can come out in the end with being OK. That’s what this is all about.”

The Gift finds its voice in performance

“These are my memories. This was my experience and understanding,” says Coast Salish artist and activist Johnny Aitken, describing The Gift, an autobiographical work of physical theatre that he both co-wrote and is co-starring in that opens today at Presentation House Theatre.

In the piece, Aitken offers insight into his personal journey towards finding his voice, all the while hoping to act as a bridge between indigenous and non-indigenous communities, as well as serve as a conduit to healing.

“It is a difficult story to tell but it is ultimately a story about overcoming adversity, overcoming a lot of violence, dysfunction. I didn’t speak until I was 18 and here I am today at 48, speaking for 30 years.. .. How do I fit into society? How do I fit in with my Indigenous community and how do I fit in with the non-Indigenous community too? With my activist hat on I think how this is what we need to do, all of us, is start working together.”

Aitken co-wrote The Gift with fellow Mayne Island resident Gail Noonan, an animator, the result of a casual conversation between the pair while riding on BC Ferries. He had offered insight into his past, his late father’s challenges with alcoholism and mental illness, and ultimately the effect posttraumatic stress disorder had on him as a young boy, keeping him silent.

“When she heard that from me, it got her attention,” says Aitken. Noonan called him a couple of days later and asked whether he would be interested in collaborating on a theatre piece. Expressing his willingness, what followed was a flood of strong memories from his childhood: growing up with six siblings and, “the death of mom when I was seven, the death of dad when I was 13 and then all the violence with dad beating my mom. Those were pivotal points,” he says.

Slowly the work, Aitken’s first, grew to its current form as a 60-minute piece. The Gift doesn’t include any dialogue, in light of his own silence for so many years, rather the story is presented through drumming, singing, vocal sounds, humour, mask, movement and dance. For the physical components of the piece, Aitken drew on his experiences as a dancer with an amateur company in Victoria when he was in his late-teens and early-20s.

Joining him for the North Vancouver performance is Shelley MacDonald, a friend and former Presentation House board member.

“It’s always been really important for me as an indigenous person to work with non-indigenous people,” says Aitken.

Writing and performing The Gift has proven helpful for Aitken’s own journey of healing. When he originally started collaborating with Noonan, he thought the process would run smoothly, that he was in a good place, however the more they delved into the process, the more he realized he still had a lot of work to do.

“At this point, after five years, what I need to do to perform this so many times is I put my professional theatre hat on and I become just an actor. It’s not me, but it is me,” he says.

To help others on their respective journeys of healing, The Gift is concluded with a talking circle.

“Gail and I felt that we needed to be responsible as artists to permit people an opportunity to share what they were feeling and to ask questions to fill in some of the gaps,” he says.

The intense and emotional piece is making its North Shore debut this weekend, running through Sunday at Presentation House. So far The Gift has been performed only in the Gulf Islands and at William Head prison on Vancouver Island.

Aitken hopes to tour the work provincially, nationally and internationally. While its message is of course of interest to indigenous people, it’s also universal in nature. He has received positive feedback to that effect with audiences expressing their take that, “this isn’t about colour, this isn’t about a specific culture. This is what many of us need to talk about -the violence, the alcoholism, the struggles, the demons,” he says.

Made possible thanks to a Canada Council grant, The Gift is the first of what Aitken hopes will be many works presented by his company, Surrounded by Owls Productions.

“I chose that (name) because I was told when I was a kid that when Coast Salish people pass away, that we all come back as owls. Being called Surrounded by Owls Productions just means that whatever I’m doing, I’m surrounded by my family, I’m not doing anything alone,” he says.

Future projects include a solo show for himself that explores his being of mixed ancestry – Coast Salish and Scottish. He’s also working on a documentary related to residential schools.

When asked how he continues to stay positive in the wake of what he has overcome in his life and where his motivation towards helping others is derived, Aitken says, “What I fill myself with is gratitude, that for whatever reason I did survive all that and here I am. How could I be anything but grateful? Every day I give thanks.”

Mixed Up

Intrepid Theatre, Victoria

Mixed-up explores the many over-lapping cultural similarities between Johnny Aitken’s Coast Salish lineage and his Scottish lineage. This production will explore Johnny’s struggles and celebrations to define his identity as a person of mixed ancestry.

Mixed up is part of the Intrepid Theatre’s YOU Show series.

Honouring Figure

This figure is based on a Traditional Welcome Figure carved by Coast Salish People. Traditionally there were two such figures in Village Sites, one male, one female. Open arms to welcome other tribe members.

This figure was carved/sculpted to Honour Emma and Felix Jack and all other Coast Salish People that visited or lived on Mayne Island. Mayne Island is part of the traditional territory of the Coast Salish Peoples.

To honour the island’s first inhabitants and the diversity of all who live and visit here, an Honouring Figure will take its place in Emma and Felix Jack Park. Johnny Aitken, a grandson of Emma and Felix Jack and a well-known artist, has carved the 20-foot figure, from a Mayne Island red cedar, over the last two years. The Mayne Island Garden Club has been the energy behind the organizing and fund-raising to make this Figure a reality.

Photo Credits: Brian Haller and Lorie Brown

Johnny with Her Honour Judith Guichon, The Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia.

Honouring Cairn

The Mayne Island Parks and Recreation Commission have agreed to have a second permanent public art installation on Emma and Felix Jack Park.

As a part of acknowledging the effects that the residential school system has had on Indigenous society and Canada as a whole the installation will be based on a burial cairn, which has been used in many cultures to honour their departed.

The installation began on National Aboriginal Day (June 21, 2016) as part of our community’s acknowledgment of this day. The installation began with the burying of a large rock, representing the residential school system. Over the buried rock were placed palm-sized rocks.

The Mayne Island school children began building the honouring cairn with their chosen rocks, some of which have been decorated.

The building of the cairn will be ongoing until it reaches its final dimensions of approximately five feet in diameter and two and a half feet in height.

Each rock will represent a child who died in a residential school or a survivor of the residential school experience. My rock honours someone I know who survived.

All community members and visitors are welcome to add a rock or two at any time, as an ongoing gesture of remembrance, awareness, and respect.

The cairn is located towards the bottom of Emma and Felix Jack Park.

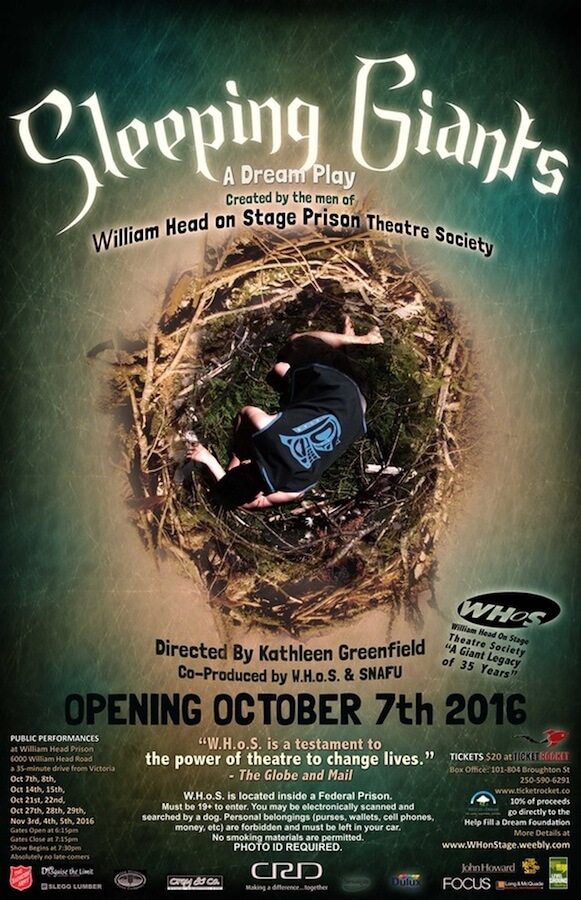

William Head On Stage

ABOUT THE COMPANY – William Head on Stage (W.H.o.S.)

William Head on Stage (or WHoS) is Canada’s longest-running prison theatre program. Since 1981, the inmates have staged a play each fall and invited the general public. Anyone 19 or older can buy a ticket, go through prison security, enter the prison gymnasium and experience the show performed by the inmates.

Sleeping Giants, a play about what happens when the world stops dreaming. Sleeping Giants began inspired by such stories as A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Rip Van Winkle, and soon grew and evolved into a wholly original piece with music, costumes, lighting, set and props–all designed and built by the inmate team. We follow the story of five human dreamers and a family of dream spirits who act as guides through the subconscious landscape. Dreams are scarce, and the dream spirits must find a way to make the humans dream again, or else fade away into oblivion.

Credit: Movement Coach

Pinocchio – Kaleidoscope Theatre for Young People

John’s debut in a speaking role was in Kaleidoscope Theatre’s Production of Pinocchio in 2018. Many thanks to Roderick Glanville, Artistic Director for this opportunity! A diverse talented and delightfully quirky cast made for a very rich and enlightening experience.